Introduction:

Global warming is driven by excessive greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which trap heat in Earth’s atmosphere, leading to rising temperatures. Among the carbon forms, CO2, CO, and CH4 are the most important. Emissions were 52.96 Gt on CO2 equivalent in 2023 alone. Even though methane has a lifespan of 12 years (compared to CO2 which has a lifespan of 100-1000 years), it still accounts for one-third of net emissions since the Industrial Revolution. The Global Methane Pledge (GMP) was proposed by the European Union and the United States of America at the Major Economies Forum (MEF) on Energy and Climate on September 17, 2021. The pledge aims to achieve a 30% reduction in global methane emissions from 2020 levels by 2030. In March 2024, GMP had a total of 158 participants.

Indian and methane:

There are two categories of methane emissions: survival emissions and luxury emissions. In the context of food security, the methane emissions are ‘survival’ emissions and not.

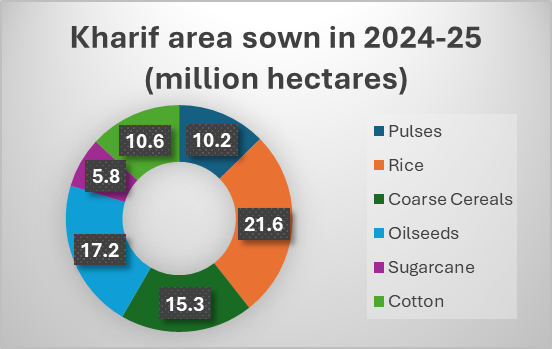

Luxury emissions. The production of methane in India is largely due to enteric fermentation from ruminants and paddy cultivation, both of which result from the agricultural practices of small, marginal, and medium farmers. The 20th livestock census of India revealed that 192.49 million cattle are rural India’s main income source. India also tops the world in rice exports, with 16.5 million metric tons in 2023-24.

Rejection from India:

India is a part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement but did not sign this Global Methane Pledge proposed. India has the highest cattle population in the world. Also, India ranks 1st in milk production and contributed 24% to global milk production in 2021-22. This agreement can be detrimental and hinder India’s ambition to become a developed country.

Rice is one of the staple foods of the world, and India is the top grower producing 1357.55 lakh tons and exporter, with a value of 896 billion, Indian rupees in fiscal year 2023. Signing this agreement will force the country to shift from irrigated lowland rice cultivation to dry-seeded rice cultivation, which is in the budding stages. Hence, it will reduce the production, exports and invariably the country’s GDP.

Conclusion:

India’s decision not to sign the Global Methane Pledge reflects its policy priorities: agricultural sustainability, economic growth, and more importantly, the interest of small farmers dependent on cattle and rice cultivation for their livelihood.

The predominant sources of methane emissions in India result from the agricultural activities of small and marginal farmers across the country, whose livelihoods might be threatened. India is currently unable to afford the extensive transformation necessary for such drastic reductions in the agriculture sector.

The need of the hour is to reduce methane emissions. India continues to demonstrate unwavering commitment towards this goal by implementing proactive strategies and measures aimed at curbing methane emissions such as the India Greenhouse Gas Pr,ogram, The National Livestock Mission, The Galvanising Organic Bio-Agro Resources (Gobar-Dhan) scheme, New National Biogas and Organic Manure Programme.

There are other cultivation methods, such as Direct Seeded Rice, which saves water during initial paddy cropping and can reduce methane emissions. Waste to Energy plants that will generate biogas from agricultural, urban, industrial and municipal solid waste, etc, are being implemented which will reduce methane emissions in the long run without compromising between climate commitments and priorities of food security, economic stability, and rural development.